For as long as motorsports have existed, competition between drivers has been the cornerstone of racing. Usually, along with the official rules there is an unwritten one called fair play. This word expresses and encompasses the values and purpose of sport; sometimes, ranging between the various sports disciplines, there are precisely unwritten rules, which transcend the regulations and which allow you to reconcile the aggressive spirits with healthy competition.

Nowadays, in car racing, in particular with GT, Touring, Formula 1 cars, etc…, fair play has taken a back seat (see for example the last race of the DTM in 2021). In simracing, in addition to lacking the deterrent against imprudence called “danger”, normally inherent in motor sports, the concept of fair play is not appreciated enaugh; and since when an accident occurs both the drivers involved have everything to lose (regardless of where the right and wrong reside), we at Trinacria Simracing in the following wanted to re-propose the concepts expressed by Randy Pobst in his guidelines on how to make a safe overtaking and to minimize the risk of collision on the track, entitled Racing Room & Passing Guidelines; these guidelines have long since been included in the regulations of the SCCA (Sports Car Club of America).

We will also talk about other useful tips to make simracers coexistence on the track more “civilized”, explaining what the irregular overtaking maneuver called dive bomb is and how to defend against it (taken from The dive bomb by Juan Pineda).

Racing Room & Passing Guidelines by Randy Pobst

Safe, successful passing is based on what drivers can see. An overtaking car bears the largest percentage of responsibly for passing safely.

Peripheral Vision

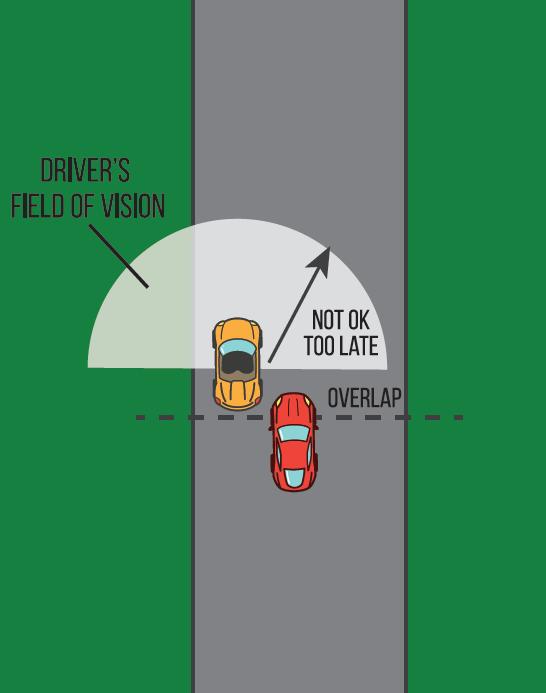

The overtaking car (the car attempting a pass) must get into the peripheral vision of the lead car (the car being passed) in the brake zone, before the lead car turns for the corner. Once the lead car turns for the corner, it can no longer see the trailing car, because the lead car’s mirrors now point outside, and the lead car must now be looking toward the apex.

The diagram above shows that the overtaking car has gotten up to the A pillar and into the peripheral view of the lead car before turn in. The overtaking car now has taken the line away and earned the right to racing room on the inside.

To earn the corner, the overtaking car must have its front end up to at least the A pillar post, or windshield, with the car under control, before the lead car turns into the corner. The goal is for the overtaking car to present itself, to arrive in the peripheral vision of the lead car, before it turns in. An overtaking open-wheel car should have its front wheel up to at least the lead car driver’s shoulder(within their peripheral vision) before the lead car begins its turn in.

The Blind Spot

The diagram above shows that at turn in for the lead car the overtaking car has yet to get even with the A pillar and into the peripheral vision of the lead car. The overtaking car is in a blind spot. Do not pass, unless the lead car is much slower and gives racing room.

Racing Room

Should the lead car decide to ‘go with him/her’, side-by-side, then both cars must allow each other racing room, at least a car width plus six inches or so, to the edges of the racing surface. In both cases, the trailing car must be in the lead car’s peripheral vision to safely hold position. If not in vision, then the trailing car must back off and follow, because the lead car cannot see it.

The biggest mistake, and a common cause of contact, is the overtaking car taking a shortcut to the apex, from that blind spot. (Turn One at Road Atlanta is classic). Pull parallel to the lead car, and as close as safely possible so that he KNOWS you’re there. Sometimes, the lead car may turn in early; therefore the overtaking car must be under enough control to avoid contact.

Passing on Straights

On straights, the lead car is allowed “one move”. It is allowed to choose a side, but cannot move back, and cannot move over in reaction to an overtaking car if late enough to invite contact. He must leave a car’s width (plus 6 inches) of racing room if the overtaking car has already committed in that direction and has achieved an overlap next to the leader.

No weaving to break the draft or to block; that’s more than one move. On straights, as opposed to corner entry, it is possible for the lead car to look into its mirrors and see the overtaking car, so if the overtaking car gets even a small overlap next to the lead car, the lead car must give the overtaking car room to race, and can no longer move across the track.

When being passed, hold your line. This means be predictable, and do not change your line to pull out of the way. ‘Hold your line’ does not mean take the line for the apex and turn in front when a much faster car is approaching. Be aware of faster traffic, and leave a lane of racing room for them.

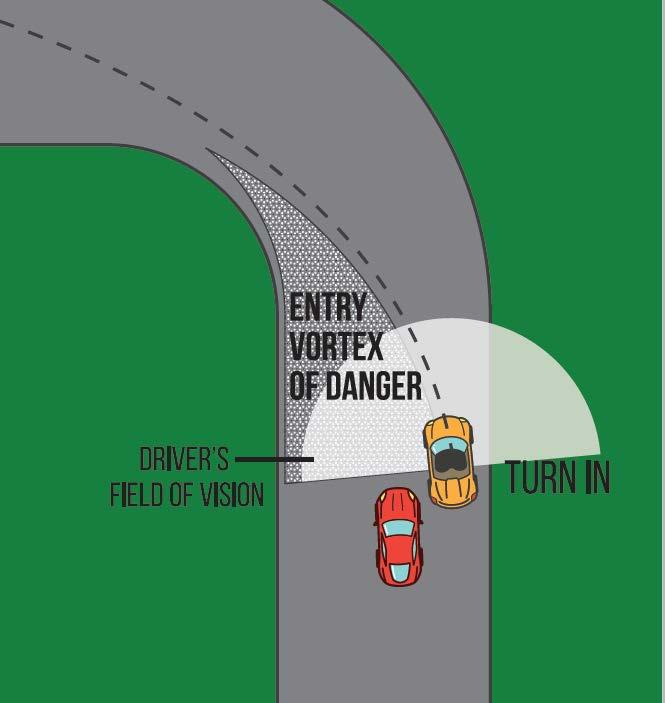

The Vortex of Danger

The Entry Vortex of Danger is a triangle inscribed by the turn-in point of the lead car, the apex, and the inside edge of the road. When overtaking, keep out of the Vortex of Danger. It’s too late to pass. The hole you see is closing rapidly, you are in a blind spot, there will likely be contact, and it will be your fault.

The Exit Vortex of Danger is a triangle inscribed by the apex, the track-out point of the lead car, and the outside edge of the road. When attempting a pass on the outside, be aware of the Exit Vortex of Danger, and back out of it if not in the lead car’s vision. It’s too late to safely pass. The hole you see on the outside is closing rapidly, you are in a blind spot, there will likely be contact, and it will be your fault.

The Outside Pass

On this outside pass attempt, the overtaking outside car never presents itself into the vision of the lead car, and cannot expect it to make room for a car it cannot see at the exit of the turn. So the outside trailing car must back off to leave racing room for the inside lead car that cannot see it, and avoid the Exit Vortex of Danger. In this situation, if the outside car makes contact or runs off the road, it is most likely their fault.

Turn 5 at Road America is a prime example of where a lead car may protect his/her line by not using all of the track on the right. The overtaking car, in this example, needs to assuredly ‘present himself/herself’ in the braking zone before turn in, the lead car is looking into the corner, not at his right mirror, and in all probability will not leave racing room at the exit. Outside passing works well when the both drivers have excellent spatial awareness but is a very low percentage move in most cases.

Remember: Safe, successful passing depends on what a driver can see. Do not hit what you can see!

**********

The dive bomb by Juan Pineda (modified and supplemented by A. Diamante)

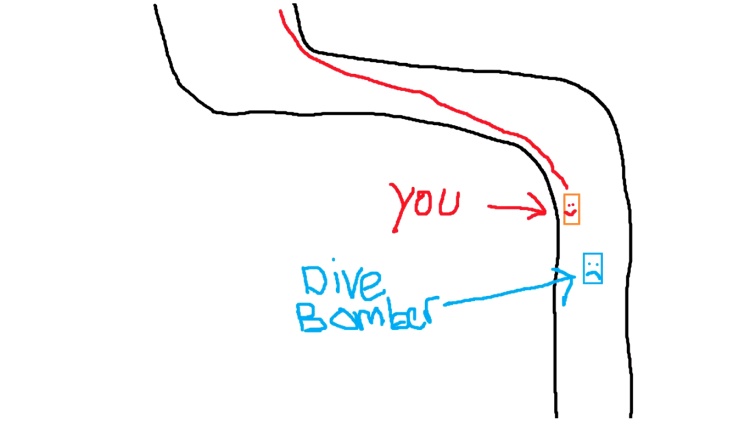

The dive bomb is a dangerously optimistic pass attempt (see for example here) that often leads to bent metal and sharp words. Why does it happen? How can you avoid being that guy? How should you defend against it?

The anatomy of a dive bomb

A dive bomb is the result of optimism, often from an inexperienced driver. This is the usual sequence of events:

- The bomber sets up on the inside passing line, but too far back for a successful pass. The victim brakes on his mark to make the corner.

- The bomber stays on the throttle instead of braking on his mark in an optimistic attempt to catch up.

- If the drivers are unlucky, the bomber makes contact as the victim turns-in, and there is bent metal to discuss in impound.

- In the luckiest case, the attacker avoids contact. But, since he is going too fast, he passes the turning point, often with blocked and smoking wheels and ends up “long” off the track (see following figure); at other times he crashes into a tire barrier or involves a third driver in an accident.

- Alerted by the commotion, the victim turns safely after the bomber flies by and the pass fails.

The physics of a dive bomb

The main principal here is that equal cars and drivers threshold braking require the same time and distance to slow for a turn. This is a fact of physics.

Let’s study a hypothetical dive bomb in a turn that requires 1.0 seconds of braking. Assume the bomber is trailing by .1 seconds. Here’s how the timing works:

- Time zero: the victim begins braking for the turn.

- Time 0.1: the bomber now arrives at the braking point (remember he was .1 seconds behind) but he does not brake yet because he wants to catch up.

- Time 0.3: the bomber has a nose at the victim’s door, and so he starts braking. He is cheering his great skill to have caught up under braking.

- Time 1.0: the victim is done braking and can turn in any time. The bomber is alongside and has been braking for .7 seconds. Unfortunately for him, he still needs another .3 seconds of braking to slow sufficiently. So he goes flying past his intended victim, often with tires locked up in a futile attempt to defy the laws of physics. The victim waits until he’s clear, then turns to get away on the fast line.

- Time 1.3: if the bomber is wise, he stays on the brakes and suffers overshooting the turn. His reward is being able to gather it up and continue, although at a disadvantage, having lost a full second to the mistake.If the bomber is unwise, he optimistically turns the wheel while carrying too much speed, and becomes an uncontrolled missile.

Advice to the bomber

A few suggestions to help avoiding becoming that guy:

- Before committing to a pass, make sure you are within striking range. A rule of thumb is that you need some overlap with the victim upon braking.

- Make sure the victim sees you by getting up to his door before turn-in. If your nose is only at the his bumper at his turn-in, then you will make contact, spin him around, and likely pay a visit to the stewards.

- Understand that you are on the inside passing line, which has a tighter radius. So you will need to slow even more than usual to make the turn.

- Watch your marks and be aware of your own braking point. If you are past it, you will overshoot the turn-in.

- Watch your speed differential vs your victim. If you are going much faster under braking, there is trouble ahead.

- If you find yourself having done the bomb, make sure to stay on the brakes and slow sufficiently to make the turn. Otherwise your uncontrolled path will be a hazard to yourself and other drivers.

- Racing is stressful and physically hard, but we still need to make good decisions under these conditions. Seat time is necessary to develop your cool.

Defending against the bomb

- The observant racer will size up the other racers and understand which ones exhibit inexperience or risky behavior. Saying hello in the paddock is helpful here as well.

- If the trailing car is on the passing line, but not within striking range, beware. The bomber is signaling his intention to carry through with the bomb. Or he might be a wily experienced racer trying to psych you out. Make sure you know which is which.

- You can try to discourage the bomber by taking a protecting line (usually the inside one; see figure below). If the bomber stays in the passing lane, double beware. The disadvantage here is that protecting is slower, so it will help the bomber catch up, and possibly egg him on.

- If the bomber is faster than you, maybe better to let him by easily so he will bomb your competition ahead. Two problems solved at once.

- Generally the best approach with a threatening bomber is to brake at your normal marker. This gives you the ability to turn under the bomber when he overshoots. Or to give him room if he gets a nose under your bumper.

- Check your mirrors before turning to know if the bomb is on. Consider giving the bomber enough room to avoid contact if there is any overlap (see here or the most famous episode on the first lap of the Abu Dhabi GP 2021 between Hamilton and Verstappen). Being in the right will be little consolation once you get turned around and lose your position.

Despite our best efforts, sometimes you get collected.

Watch the rear view mirror for the bomber and note his speed differential vs his victims. As you see, there was a big melee in which many cars checked up, so probably the bomber became excited because he found himself coming through traffic with a big speed advantage and so lost his reference for turn.

In racing you sometimes get collected. Make sure to calmly talk through what happened with the other driver. Watch the videos. If you are the bomber, better to listen and take responsibility for your contribution, and learn from the bomb so it doesn’t happen again. Both parties: do not be shy about taking it to the stewards if you can’t come to agreement about responsibility.

Please note: with regard to overtaking side by side near the turning point, we at Trinacria Simracing believe that, in order for these to be understood to be correct, it must always be brought in complete wheel-to-wheel flanking before the braking zone (cit. “Fully alongside wheel the wheel before the braking zone”), to be understood, in the most widespread interpretation, the matching of at least half of the overtaking car with the overtaken car.

Remember: most accidents are caused by the fact that a driver has not adequately developed one of the indispensable qualities in racing (and especially in endurance racing): patience (regarding the mistakes made during overtaking, in this video Scott Mansell puts lack of patience first). If you are faster, caution is often the winning weapon. Brake a few feet earlier to follow a slower car through a corner instead of forcing your way through or attempting a last-second dive bomb. At best these dive bomb moves will slow both cars down through the corner as you drive side-by-side, at worst, when an accident does not occur, the few tenths you might have gained will be offset by a penalty and the risk of driver probation. Respect for your fellow racers is required (it also and above all passes through patience). We are all responsible not only for the outcome of our race but also, with our behavior on the track, for the outcome of the race of our fellow competitors; therefore, work on yourself if you are unable to be patient.

Caveat

The aforementioned tips are of a general nature and putting them into practice, in any case, will improve your driving experience, both in the minor categories of real car competitions and in simracing; however, keep in mind that each racing series and / or community can have different standards in terms of regulations.

TRINACRIA SIMRACING – PARTNER OF OMEGAMOTORSPORT ITALIA